The ongoing exhibition on architect Alfred Weissenberg is the first to present his lifelong work as an architect and artist in its entirety. Sörmlands museum holds the complete archive of his drawings in its collections. Together with art and photographs from the Weissenberg family, it provides an insight into the work of an architect in the mid-20th century. The material is also the start of a third generation's exploration of their Jewish family history.

Alfred Weissenberg's austere design language, where form follows function, has been compared locally to that of the famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. In close cooperation with the clients of the houses he designed, Weissenberg created a poetic but solid architecture that reflected the personality of the owner. Living in a Weissenberg villa is special. In recent years, some enthusiastic families have created the Weissenberg Society.

What characterizes his later work and captivates the viewer is his feeling for all kinds of tasks. It may seem that he identifies with the soft approach of the 1940s, being sensitive in his choices, detailing and material changes.

Fredric Bedoire, architectural historian

Alfred Weissenberg was of Jewish origin. He lived at a time and in a Europe largely characterized by the persecution of Jews. We do not know how this affected Alfred on a personal or professional level. Still, it was a reality that all Jews had to cope with. Just like today.

Caring for the beautiful, in the shadow of persecution and world wars

Alfred Weissenberg was born on November 21, 1899 in Brandenburg, Germany. His parents were from Prussia in Germany, and the family came to Sweden in 1903. The family's history in Sweden can be followed through Mosaic and Swedish Church parish records. They settled in Stockholm and the father ran a clothing store.

Alfred Weissenberg studied at the Technical School (now Konstfack) and the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. 1922-1925 he was employed by the architects Isac Gustaf Clason and Gunnar Asplund.

He was an urban planner in Malmö from 1926 to 1928, and then went on to study at the Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, where he worked as an architect until 1940. During the Nazi occupation of Denmark, he, like many other Jews, fled to Sweden. He moved to Flen in 1941 where his brother and his family lived. The brother ran the clothing industry Nyma AB. Alfred Weissenberg settled in Nyköping in 1941 and lived there until his death in 1977.

The nearest synagogue and Mosaic congregation was in Norrköping, but he probably lived a secularized life with his fiancée Karin, who was a nurse. Alfred Weissenberg drew and painted throughout his life and had a close relationship with his siblings with families in Flen and Stockholm.

Alfred is described by the family as a warm and friendly uncle and great-uncle. The siblings' grandchildren who visited Alfred while passing through Nyköping remember him as happy and funny. Nyköping residents describe him as a handsome man with a bow tie who was seen walking with the dachshund Larsson.

Education

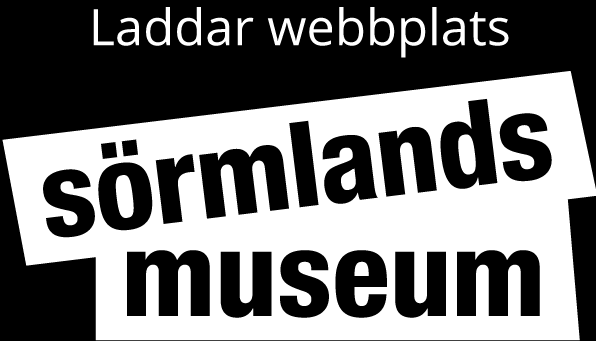

These sketches are from Alfred Weissenberg's time at the Technical School. He studied at the department known as Byggnadsyrkesskolan 1915-1918.

The sketches provide an insight into architectural education in the early 20th century. There are drawing studies of various kinds, staircases, vault constructions, wall joints, shadow studies, perspective studies, sections of different types of houses, pattern studies and more. Everything is meticulously drawn. There are also pure art studies that seem to have been part of the education.

Alfred also studied at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology and later at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen. This was a solid foundation for a future architect, which undoubtedly influenced his entire professional life.

Copenhagen villas

The villas Alfred Weissenberg designed in Copenhagen display the evolution of his style during the 1930s. Early projects still used traditional stylistic features and were influenced by 1920s classicism. Gradually, modernist tendencies take over and shape everything he draws.

Some of the most pure examples of modernist architecture from this period exist. Alfred was heavily influenced by the functionalist design language that emerged at the 1930 Stockholm Exhibition.

COPENHAGEN, 1930-1940

During his time in Copenhagen, Alfred Weissenberg worked on a wide range of projects, from large to small. These include public buildings and large apartment building projects as well as villas, kiosks, shops and interiors. The drawings from the period also show a search for his own design language.

Craftsmanship and artistic talent were important qualities for an architect. A well-crafted set of drawings was both a way of selling an idea and demonstrating competence for the task. Alfred's drawings from the 1930s are carefully prepared and often accompanied by coloured sketches or watercolours. It is not clear how many of the projects in Denmark were realized, but a number of houses still exist today.

Many of the design elements that emerged during this period recur throughout Alfred's career. Here we see, for example, basement railings with parallel round steel that curves down to the ground, rhombic patterns in doors and facades, accentuated stairwells and the round windows. His feeling for different materials is also evident here - not least the brick.

For Weissenberg, the modernist style becomes more and more refined over the course of the decade. However, he also experiments with its forms. Alfred has an ability to soften many of the often mechanical and objective expressions to become more human. This can be seen not least in the colour scheme, which is often strong with rich and warm tones. This is another aspect that will remain throughout his career.

Nyköping

In December 1941, Alfred Weissenberg settled in Nyköping. Even then, he had a handful of commissions that were completed during the year. Among the first houses he designed in Nyköping were two apartment buildings and a villa on Villavägen. The villa was one of a total of nine that he designed in the area in the following years.

The first period in Nyköping, Alfred Weissenberg lived at Slottsgatan 5. His home was also his office. In 1945 he designed an apartment building on Östra Kyrkogatan. When the building was completed, he moved into one of the apartments. Shortly thereafter, he designed a new office and residential building for Södermanlands Nyheter at Östra Storgatan 6. Alfred once again moved into the house he had designed. He remained here for the rest of his life.

Alfred himself became a recurring feature of the urban environment around Östra Storgatan where he walked his dog, the dachshund Larsson. Although work probably took up most of his time, he never let go of art, which continued to be a central part of his life. He painted landscapes and buildings but was also involved in an art group that met regularly and drew kroki.

Alfred never employed anyone. However, he took on trainees who followed him for a year or so. He was described as friendly and kind, but very thorough. Erasers and pencil sharpeners were banned - the pencil had to be twisted when the lines were drawn so as not to become blunt. When the workday began, the trainee's first task might be to stove away Alfred's newly painted artwork from the night before.

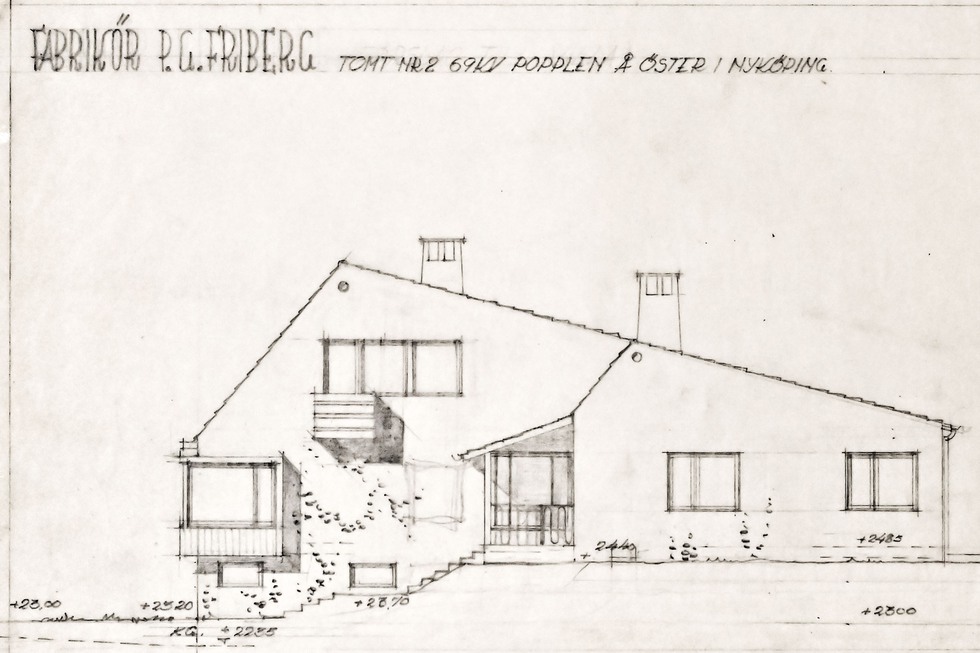

Apartment buildings in Sörmland

Alfred Weissenberg designed a large number of apartment buildings around Sörmland. They can often be recognized by certain distinctive details.

The first apartment buildings he designed in Nyköping are located at Stockholmsvägen and Tullportsgatan. The house on Stockholmsvägen is a large three-storey functionalist house just on the edge of the old town. The front is symmetrical with long, regular rows of windows, with small semi-circular balconies at the end of each row.

Balcony fronts of punched sheet metal were used by Alfred in several houses. This was very unusual at the time. A centrally located entrance with a heavily plastered surround is located at the front of the house. We find the same type of entrance on the apartment building at Tullportsgatan. Here, however, the large round window is the focal point. With its peculiar glazing, it is reminiscent of a church window.

Alfred Weissenberg's designs can be recognized by certain features, which he used recurrently. The round windows and the round steel basement railings that curve down to the ground are obvious characteristics. Most of the stairwells have stair railings with characteristic wave-shaped slats of the same type.

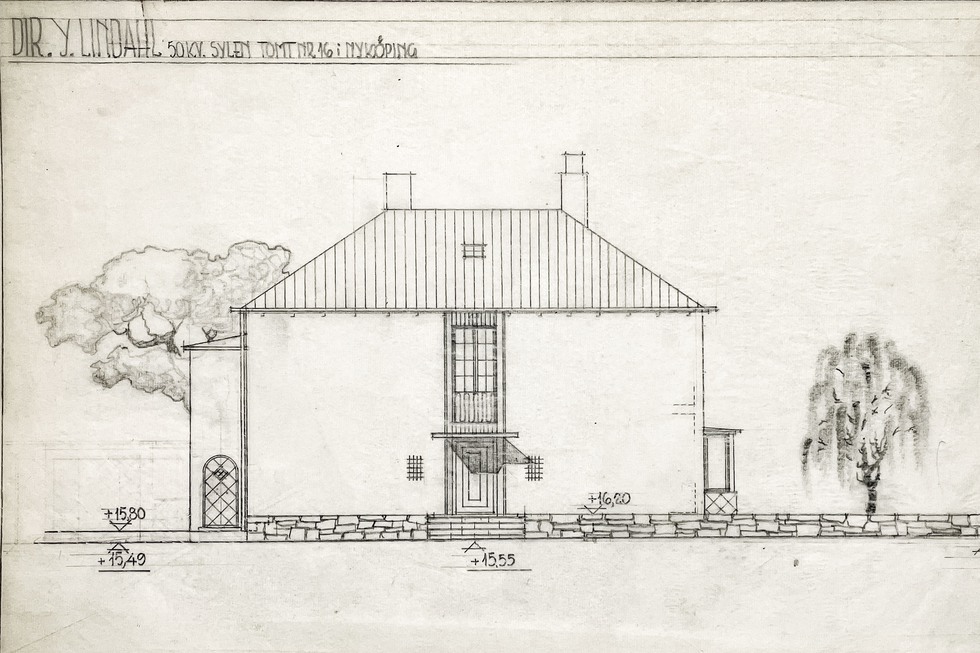

The villas

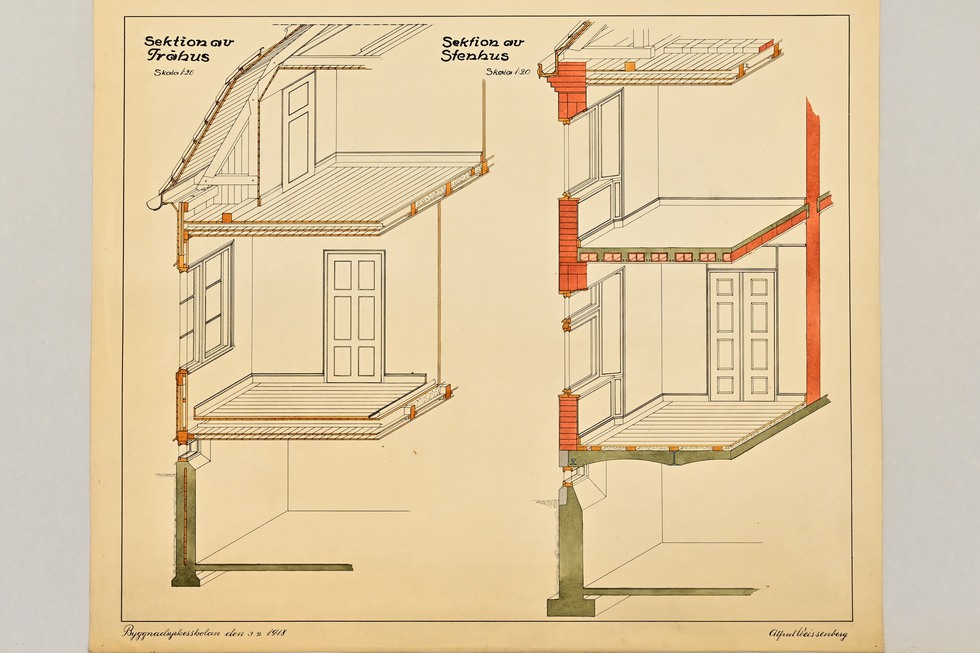

Alfred Weissenberg was a frequently hired villa architect. During his time in Nyköping, he designed around 20 villas. A commission to design a villa did not mean that the work was finished when the drawings were delivered. Alfred was very careful when his ideas were realized and often had opinions on the execution of various details. Each assignment was individually adapted to the specific situation or client.

The villas in Nyköping are generally simpler than those he designed in Copenhagen. The austere modernist idiom that characterized the Copenhagen period has been softened somewhat, becoming more traditional. Flat roofs have been replaced by gable roofs, but great emphasis has been placed on the interiors, which typically contain several distinctive features.

Alfred was very thorough with the fireplace. No two were the same. The location in the home varied, as did the materials and how the fireplace was adapted to the wall. Each piece is carefully designed, and his playfulness shines through with cleverly designed damper handles and firedogs.

Several of the villas have an additional outdoor fireplace on a terrace or patio. The outdoor environment and gardens were an important part of the whole. There are also glazed rooms or bay windows for plants, and consequently many of the villas still have a modern feel to them.

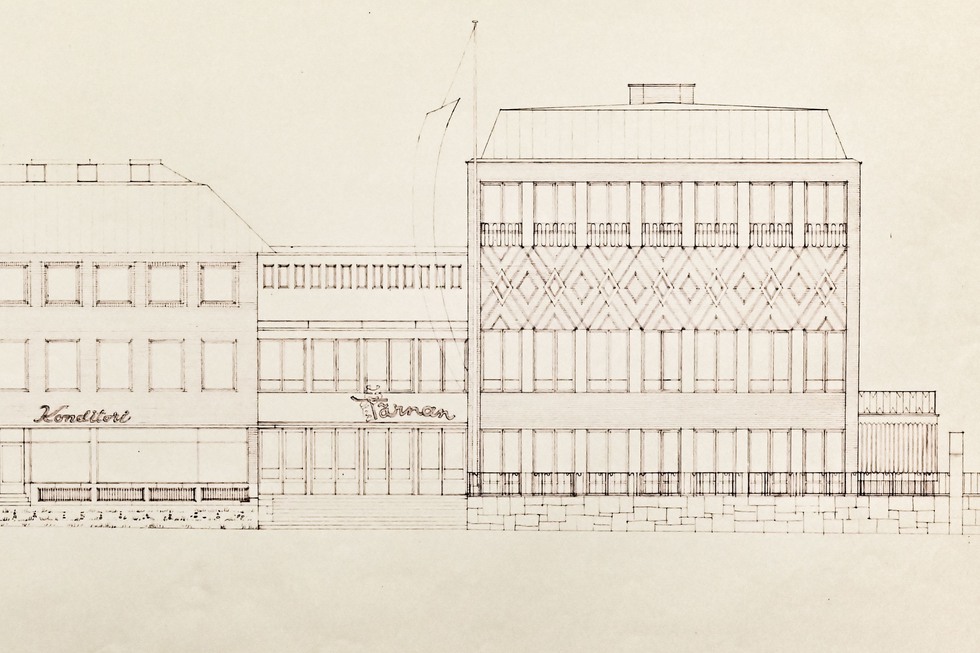

Folkets hus in Oxelösund - a peak of Alfred Weissenberg's career

In this project he fully demonstrated his sensitivity to design, materials and layout. Every part of the building was carefully considered and lavishly decorated with exclusive interiors and materials.

Folkets hus was a project that Alfred Weissenberg followed for many years. As early as 1949, he made the first sketches of the building. He decided early on that the building would consist of two separate volumes with a smaller intermediate entrance area. The theatre part was the most prominent with larger windows and decorations.

Inaugurated in 1956, Folkets hus quickly became a hub of the city's cultural and entertainment life. Ideas for a Folkets Hus had been around since the 1930s, but it took almost 25 years for the plans to become reality. When the building was finally completed, it was immediately filled with a wide range of activities.

The left-hand section with red brick facades contained a bank, a bakery and café, a library, meeting rooms, study rooms, offices, overnight rooms and a complete apartment on the top floor. The entrance area led to the Tärnan cinema and theater in the yellow-bricked building. A large and spacious foyer with a curved staircase brought visitors up to the cinema and theater on the second floor. The auditorium had a seating capacity of about 400.

A separate entrance and staircase at the end of the building led to the Cupol dance palace on the top floor. Cupol could be used independently from the other floors. In the basement, there was a state-of-the-art bowling alley with sensors to detect violations.

The foyers, with their patterned marble floors, custom-designed furniture and curved staircase, stood out among the interiors. The magnificent light and dark wood framing of the theatre stage also showed Alfred's sense of material and form.

Convalescent home in Malmköping

The building in Malmköping was the next major assignment after Folkets hus in Oxelösund. The drawings for the two buildings were partly executed in parallel and similarities can be seen in both the layout and design.

Convalescence, or recovery, was an important part of the healthcare system throughout the 20th century. At the end of the 19th century, the first convalescent homes were established to allow patients to recover from major surgery or illnesses that did not require acute hospitalization. The convalescent home at Plevnahöjden in Malmköping was opened on March 6, 1957. There was room for 25 people who usually stayed at the home for three weeks.

The home consisted of three interconnected buildings - two for patients and the third for staff. The patient rooms were in pairs and shared a common cloakroom and toilet. In addition to 19 single rooms, there were three double rooms in the far west. On each floor there were lounges with fireplaces. On the ground floor there was a large dining room and guild room. The home and a shared patio overlooked the valley below.

Despite the somewhat austere and matter-of-fact exterior of the convalescent home, there is a playfulness in the design of details. Examples include the three types of stone flooring in the entrance hall, the concrete glass skylight in the western stairwell, and the new moon-shaped damper handle for the fireplace in one of the sitting rooms. The most eye-catching feature is the patterned flooring in the guildhall. Here Alfred used green, brown and white stones to create a savannah landscape with trees and a giraffe! The fact that the lodge is two steps lower than the dining area in the same room means that the motif can be viewed from above.

An uncertain future

Despite high quality and stand-out details, the houses designed by Alfred Weissenberg do not always have a secure future. Many of his villas are highly appreciated by their owners. However, a large number of houses have already been demolished, and others have undergone careless changes.

Unfortunately, the functionalist buildings of the 1940s and 1950s still have a low reputation, as they are often considered unremarkable and without obvious artistic qualities. This is a misconception. Stylishness and simplicity were key features of functionalist architecture. Proportions, material treatment and detailing were therefore important aspects of the whole. Careless changes to windows, doors or facades can easily be devastating in this type of architecture.

The door on the right comes from a laundry designed by Alfred Weissenberg in 1948. Located on Rättarvägen in Nyköping, the building was demolished in 2022 without any investigation or assessment of its cultural value. By pure coincidence, we walked past the house before the door was thrown away, and could therefore include it here.

The door is very typical of Alfred Weissenberg. He often used the rhombic patterns in his doors, which is evident on many of the houses he designed throughout his career. Often they are also round-arched at the top.